This week I have been reading two books ResoluteReader led me to. One is a volume from George Macdonald Fraser's Flashman series (more about which in another post.) The other is an old Philip Pullman I found in that second-hand place near Plaza in Connaught Place. Two years ago RR actually sent me his lovely copy of The Golden Compass, first book of the gripping trilogy His Dark Materials , prior to which I was woefully ignorant of Pullman's existance. The trilogy has attained cult status appearing in every list of books from the Guardian's 100 Books You Can't Live Without club to the I-Am-So-Cool list trotted out by the slightly drunk geek who was hitting on you last week.

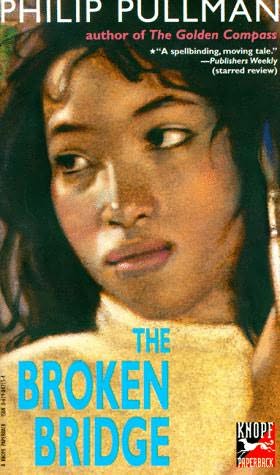

Pullman was writing for children and young adults a long while before His Dark Materials was raised to the canon. Broken Bridge is one of these older books (ten years older than HDM) and clearly meant for teens and young adults, while the HDM triology has the inexplicable crossover quality that brilliant children's books have. Broken Bridge is set squarely in Wales where 16 year old Ginny Howard lives with her father. Ginny's Haitian mother died when she was a child and she has grown up as one of the two black children in a shiny white small town. Even Ginny's father is white, something that troubles her occasionally, despite the excellent relationship she enjoys with him. Ginny's great sense of pride comes from having inherited her mother's artistic abilities. Ginny sees a future as an artist very clearly. When the story begins she is pursuing both art and French passionately and exploring the implications of being a black artist in a predominantly white country. Does she, as a black artist necessarily see things differently? While these questions are being mulled over there are still friends, her father, a familiar and beautiful landscape to paint and the summer to enjoy.

When things get shaken up, they get shaken up in a big way. She discovers that the two boys she has grown up flirting and hanging out with, have big secrets of their own. Her best friend has a sister she did not know about. Worse, she herself has a half-brother roughly her own age who she never knew existed. Why is Joe Chicago, the gangster involved in her life suddenly? Is it true that her father has been in jail? And who are the strange people she remembers living with as a child? Broken Bridge's fairly straight-forward coming-of-age narrative is beautifully written in Pullman's strong, clear prose. Visual details are particularly vivid in this book as they are seen through Ginny's eyes.

The paintings described in the book are extremely seductive. but there is very little of the fantastic or supernatural in this particular book unlike HDM. The two episodes of that ilk that do exist are extraordinary. One, the appearance of Baron Samedi, coolest of the loa (the spirits of the voodoo) a spirit dressed in a top hat, black tuxedo and dark glasses. If there must be the supernatural, let it be thusly wonderful. The second episode dried my mouth for its rapid and terrifying transformation of that most benign of objects: a grandmother. In this bit, Ginny is having tea with her grandparents and her tiny, white-haired grandmother turns into a raving, foam-flecked loony, in response to an unknown cue.

Pullman takes the inner lives of children very seriously, as seriously as children themselves do. Pullman's children and adults share parts of their lives with each other but are independent entities. Adults are not all evil or all kindly. Their motivations sometimes coincide with what the child would like or might be in the best interest of the child, but sometimes do not. Ginny like Pullman's better-known heroines Lyra Belacqua or Sally Lockhart is very sure of her place in the world and what she will do to retain that place. A fine mixture of ruthlessness and compassion makes them very fascinating protagonists. Pullman is one of the few authors I have read who has managed to combine the startling possibilties of childhood with its equally dramatic menaces. He is widely quoted for his criticism of books that deify childhood. 'I hate the Narnia books, and I hate them with deep and bitter passion, with their view of childhood as a golden age from which sexuality and adulthood are a falling away... I was looking at old copies of Punch , when it was infused by A. A. Milne's influence - all those beautifully drawn pictures of cutie little children that would never grow up, being sweetie little things to their mummies and daddies.' Even so, his vision of childhood is nowhere as frightening as the world Margaret Atwood creates in Cat's Eye in which she says 'Little girls are cute and small only to adults. To one another they are not cute. They are life-sized.'

Pullman has earned a good deal of criticism for what is seen as violent atheism or even Satanic messages in his book. One very troubled critic who called him the most dangerous author in England, had this panicked query: If there is no God in Philip Pullman's world, then who makes the rules? Well, well, now, now, there, there. I think his characters will bumble along, tough little gits that they are.

0 comments:

Post a Comment